“Online Proctoring: All Day and All of the Night!”

“Live Online Proctoring Redefined!”

“Switch to the Gold Standard” (of student proctoring)

“Making Any Mode of Proctoring Possible.”

“Make Them Prove They Aren’t Cheating!” (okay, I made this one up)

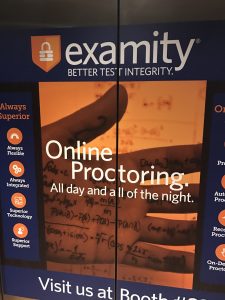

These slogans and their accompanying images are the gatekeepers standing in between me and the conference upstairs. If attendees use the escalator, they will be greeted at the top by the image of an all seeing eye. If they choose the elevator, the doors close and form a gigantic hand hand, covered in mathematical formulas; presumably it’s the hand of a cheating student, trying to pull a fast one on their professor. But quickly I learn that professors have nothing to fear if they only buy “Examity,” which promises “better test integrity” all done in service of students who want to succeed the “right way.”

If the entry into the registration/vendor space of the conference is any indication, students are rampant cheaters and can only be stopped by the vigilant vendors, ever-ready with their surveillance tools. The emblems of these companies are equal parts creepy and unintentionally ironic: a lock and shield; what I think is supposed to be a webcam, but it more closely resembles a bathysphere or the head of a deep sea diving suit, and a giant owl with a graduation cap. I imagine designers thought a peephole or a gigantic pair of eyes bulging through a computer screen were too obvious (or perhaps those images are already taken).

Several essays in recent weeks offer important insights that are useful in thinking about this setting. Audrey Watters talks about how we confuse surveillance with care.

Joshua Eyler, in an important essay, recently wrote about what seems like weekly appearances of essays that deal in student shaming.

Jesse Stommel also addresses student shaming, and the implications for doing so. He writes: “We can’t get to a place of listening to students if they don’t show up to the conversation because we’ve already excluded their voice in advance by creating environments hostile to them and their work.”

These issues matter, and what I would add to them is the issue of student framing; in other words, how are students imagined when we attend a conference? Who do we think our students are? Who do vendors think our students are? What is their investment in getting us to imagine students in that way? Certainly there are other ways to assess students that don’t involve forcing them to be watched either by an algorithm or some unknown proctor on the other end.

Along with the privacy issues (some of which are discussed here and here), subjecting students to this kind scrutiny casts every student in the role of a potential cheater. So not only is it invasive, in terms of pedagogy, it sets up the classroom as a space where every student is trying to put one over on the professor. This is hardly ideal pedagogy or a sound way to set up trust in a classroom.

I’ve written before about the absence of student voice in conferences (here) and it’s clear that this space is not one that was designed with students in mind, but the question I have is this: what is the effect of attending a 3 day conference where the looming image is one of the dishonest student? Is this where “Innovation” takes us—optimizing the spying capabilities of educational institutions? Silicon Valley would be proud.

Any relationship is first about trust. Education in particular requires trust. Trust in information being presented. Trust in the integrity of the teacher and the institution. Trust that there will be some payoff, often far down the road. Trust in so many different facets that it is impossible to untangle. There is either trait or there is not trust. Often time a first and continuing evidence of lack of trust is in the procedures surrounding testing.

Quick story… I was getting a CS degree and taking an education course because it is an area of interest for me. I was doing well and had finished my final project. That’s how far along we were. The prof has asked students to prepare a draft of something or other with very loosely defined requirements. Drafts were returned and discussed. She called several students out for what she considered to be glaring mistakes though nothing outside of the parameters of the assignment. (I was not one of them.) I immediately scheduled time, discussed the issue (respectfully) and declined to finish the course. It required that I delay getting my degree for a semester. I didn’t trust her at that point and wasn’t going to put myself in the position of relying on her judgement or integrity. That was that.

Monitoring does not engender trust in the party being monitored or the one doing the monitoring. It is inherently adversarial and there are many well established biases that come into play.

Thanks for that story. It can’t be overstated how much trust matters in education, and surveillance tools that have as their basic assumption that everyone is dishonest are bad pedagogy and disruptive in all the worst kinds of ways.

Great post Chris. I gave a erosion with Jim Groom last year where we critiqued Turnitin.Com and asked the audience what its ethos was. A colleague of mine captured in the well “catch me know if you can”. What we do when we use these tools is communicate mistrust to our students and kinda promote focus on gaming the surveillance or self-surveillance. Foucault would be proud. And I WILL DM you something else…

[…] problem related to students at the conference was how they were framed as cheaters at every turn. Chris Gilliard wrote a blog post that explores this aspect in depth. I was able to finally meet and hang out with Chris and many others at Innovate. Those of us that […]

Thanks for sharing your thoughts on this, Chris.

I too was taken aback about the messaging, and even more slightly disturbed about the messaging about how we need to “watch” or be “en guard,” with regards to our learners. My enlightening moment arrived when I was explaining to a hotel employee what proctoring is in the elevator when the elevators doors closed … then awkwardly laughing at the weird way it was being advertised or marketed for educators.

I am not sure why we are letting platforms or vendors dictate our “trust” or how we develop a community of learning in digital environments when there are issues of shaming, trolling, spamming and the like. Or considerations for how certain open and social technologies make affordances that not all of our campus stakeholders can take advantage of… but this is often left aside in our pedagogical planning.

We have talked about this before and probably should discuss this again, that our students care more about their data and the places they are “seen” for online/blended learning experiences. When do we take their input into account? Why aren’t we thinking about developing community learning standards with our students? What considerations should we speak more to or about for online learning?

Shout out to Maha who spoke a great deal about this last week in her #OER17 keynote:

https://oer17.oerconf.org/sessions/keynote-maha-bali/

This conversation is not over… let’s keep talking/informing/sharing.

These are all really important and insightful questions, Laura! Thanks for commenting. I’ve been thinking about this a LOT since I wrote this post. The notion of who gets to set the tone at conferences is something I hadn’t considered much before OLC, but I think it’s something we all need do work on moving forward. Vendors (at least in theory) are responding to a “market” (ugh, yes I just used that word) they shouldn’t be creating it, especially when what they create is detrimental to students.