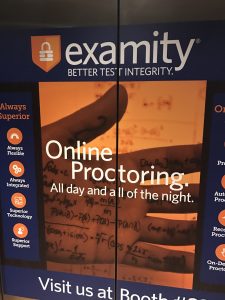

“Online Proctoring: All Day and All of the Night!”

“Live Online Proctoring Redefined!”

“Switch to the Gold Standard” (of student proctoring)

“Making Any Mode of Proctoring Possible.”

“Make Them Prove They Aren’t Cheating!” (okay, I made this one up)

These slogans and their accompanying images are the gatekeepers standing in between me and the conference upstairs. If attendees use the escalator, they will be greeted at the top by the image of an all seeing eye. If they choose the elevator, the doors close and form a gigantic hand hand, covered in mathematical formulas; presumably it’s the hand of a cheating student, trying to pull a fast one on their professor. But quickly I learn that professors have nothing to fear if they only buy “Examity,” which promises “better test integrity” all done in service of students who want to succeed the “right way.”

If the entry into the registration/vendor space of the conference is any indication, students are rampant cheaters and can only be stopped by the vigilant vendors, ever-ready with their surveillance tools. The emblems of these companies are equal parts creepy and unintentionally ironic: a lock and shield; what I think is supposed to be a webcam, but it more closely resembles a bathysphere or the head of a deep sea diving suit, and a giant owl with a graduation cap. I imagine designers thought a peephole or a gigantic pair of eyes bulging through a computer screen were too obvious (or perhaps those images are already taken).

Several essays in recent weeks offer important insights that are useful in thinking about this setting. Audrey Watters talks about how we confuse surveillance with care.

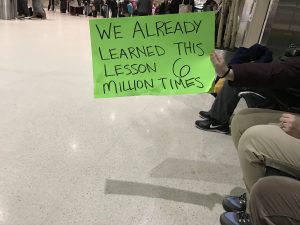

Joshua Eyler, in an important essay, recently wrote about what seems like weekly appearances of essays that deal in student shaming.

Jesse Stommel also addresses student shaming, and the implications for doing so. He writes: “We can’t get to a place of listening to students if they don’t show up to the conversation because we’ve already excluded their voice in advance by creating environments hostile to them and their work.”

These issues matter, and what I would add to them is the issue of student framing; in other words, how are students imagined when we attend a conference? Who do we think our students are? Who do vendors think our students are? What is their investment in getting us to imagine students in that way? Certainly there are other ways to assess students that don’t involve forcing them to be watched either by an algorithm or some unknown proctor on the other end.

Along with the privacy issues (some of which are discussed here and here), subjecting students to this kind scrutiny casts every student in the role of a potential cheater. So not only is it invasive, in terms of pedagogy, it sets up the classroom as a space where every student is trying to put one over on the professor. This is hardly ideal pedagogy or a sound way to set up trust in a classroom.

I’ve written before about the absence of student voice in conferences (here) and it’s clear that this space is not one that was designed with students in mind, but the question I have is this: what is the effect of attending a 3 day conference where the looming image is one of the dishonest student? Is this where “Innovation” takes us—optimizing the spying capabilities of educational institutions? Silicon Valley would be proud.

6 Comments